Cuba

Hoy no hay nada

December 26, 2024

Times of Crisis

The first thing I noticed when I arrived in Havana was also the last thing I noticed before I left: long lines. People lined up in front of stores. Cars lined up at gas stations. Passengers lined up at bus stops. Lines are usually an indicator that demand exceeds supply. In Cuba, this imbalance is everywhere. There are shortages of fuel, food, and other consumer goods.

The country literally cannot import enough oil to keep its economy running. Unlike in other countries, the problem is not that oil and other goods are available but are just too expensive for large segments of the population. In Cuba, there is simply almost no oil. Gas stations are regularly out of service for days at a time.

During our time on the island, the phrase we heard almost daily was “Hoy no hay nada” – “Today there is nothing”. Whether it was in restaurants where 95% of the menu items were unavailable, in tourist destinations where certain activities were not offered, or in stores where shelves were almost empty.

How did Cuba end up in this precarious situation? After all, in the 1950s it was one of the most advanced economies in Latin America. Aren’t we living in a globalized economy where basic goods are widely available? Well, they are… unless a country dares to confront the U.S., the self-proclaimed hegemon of the world.

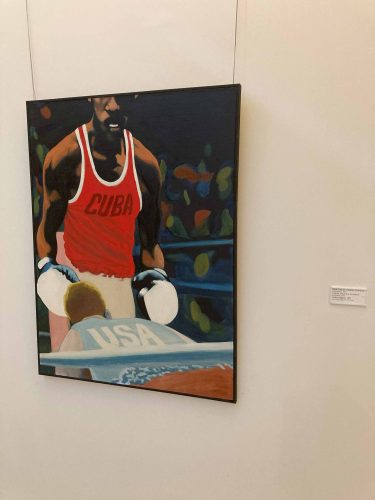

David versus Goliath

Cuba’s history reads like a modern-day version of David versus Goliath. After more than 400 years of colonial rule, Cuba gained independence from Spain in 1898. However, “independence” initially meant that the country was handed over to the United States after the Spanish-American War. Although Cuba became formally independent in 1902, the U.S. retained the right to intervene in Cuban affairs and support U.S. economic and political interests for decades to come. American-owned hotels and restaurants catered to the tourist boom of the 1920s, and by the 1950s, more than half of Cuba’s lucrative sugar industry was owned by Americans.

When Fidel Castro and his supporters overthrew the government in the 1959 revolution, they quickly changed the face of the Cuban economy. The state nationalized all U.S.-owned companies and declared ownership of the entire industrial and manufacturing sector. The Agrarian Reform Law expropriated thousands of acres of farmland, including the property of U.S. landowners.

The U.S. responded immediately by imposing economic sanctions that effectively prohibited trade between the two countries. In 1962, the Organization of American States, under pressure from the U.S., imposed similar sanctions on Cuba.

The U.S. embargo against Cuba, which remains in effect today, is the longest-running trade embargo in modern history. Officially in place to pressure the Cuban government toward “democratization and greater respect for human rights,” the embargo has been routinely criticized by the UN General Assembly, which has passed a resolution every year since 1992 calling for an end to the sanctions and declaring them a violation of the UN Charter and international law.

While it would be shortsighted to blame U.S. sanctions alone for Cuba’s economic hardship, they have undoubtedly posed and continue to pose significant challenges to the Cuban government. Faced with international isolation, the country turned to the Soviet Union in the 1960s, establishing trade relations that would flourish for decades to come. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 plunged the country into a major crisis known as the Special Period. By 1995, Cuba’s GDP had shrunk by 35%, leading to severe food and fuel shortages.

According to many Cubans we spoke with during our visit, the current situation is as bad as that “Special Period”. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Cuban government reorganized its economy once again, turning to Venezuela as a reliable supplier of oil. In doing so, they paradoxically benefited from yet another U.S. embargo that prohibited U.S. oil companies from purchasing oil from socialist Venezuela. With the escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War in 2022, however, this ban was quickly lifted, making the price of Venezuelan oil skyrocket beyond what Cuba could afford.

Resilient but at a Crossroads

But Cuba wouldn’t be Cuba if it collapsed under these enormous pressures. The Cuban society has developed a level of resilience that few others in the world can match. With a mix of creativity, solidarity, and discipline, people help each other in times of need, share what they have, and build, grow, and repair as much as they can. The best-known symbol of this spirit are the 1950s vintage cars that make up a large part of the island’s fleet. From Cienfuegos to Trinidad, for example, we traveled in a 1958-built car that made alarming noises every time the road got a little steep. And indeed, at one point it broke down – only to be fixed by our driver within 15 minutes.

The socialist Cuban government has an impressive track record. Cuba’s health care system is among the best in the world, with one of the highest doctor-to-patient ratios (more than double the U.S. rate) and one of the lowest infant mortality rates (lower than the one of the U.S.). Within a few years of the revolution, the government raised the literacy rate from 77% in 1959 to over 96%, the highest in Latin America. Internationally, the country participated in several wars, playing a crucial role in the struggle against South Africa’s apartheid regime and supporting North Vietnam during the Vietnam War. Considering Cuba’s size, the geopolitical role it has played in recent decades is remarkable.

But as impressive as these achievements are, they are not enough to help the government in the current crisis. The younger generation in particular is increasingly fed up with a government that responds to the slightest protest and opposition with fierce repression. Exposure to the internet and social media increases demands for a “Western” lifestyle and reduces tolerance for the hardships caused by the strict regulation of resources and consumer goods.

As a result, more and more Cubans are trying to leave the island. Many have sold their homes to buy a one-way ticket to Nicaragua, hoping to somehow make it to the U.S. via Mexico. In just one year, the number of Cubans trying to enter the U.S. from Mexico has increased about sevenfold. Once again, Cubans must stand in line – this time not in hope of a gallon of gas, but in hope of a new beginning.

Note: This blogpost is based on a visit in June 2023.