Malawi

God is always good

May 21, 2018

By now, six weeks have passed since my arrival in Malawi. Meanwhile, the excitement of the first days has settled a bit and a daily routine has established. For my work, things are going surprisingly smoothly and I advance more or less according to the schedule that I had set up before coming here. That alone led to great surprise among people who have been working here for a while.

There have, however, also been some struggles with the project: I hire pit-emptying businesses which empty the pits of the households while I take the sample. These are small businesses with only a few people and the minimum required equipment. Normally, they only get a few orders per month, which means that our order (40 households within 4-5 weeks) is a really big fish for them, worth around 1500 €. So, if I were in their position, I would do everything possible to make sure I get the full job and can empty all 40 households. With the money you earn, you can maybe buy your own truck, develop your business further, whatever. What happened, however, was the following: Pit emptier #1 gave us a good price per household in the beginning, which is why we hired him. Subsequently, he came every second day asking for more money because something “was not as agreed in the beginning” (which is in some sense true, but the amount of extra money he demanded was just ridiculous). Next, two days in a row we had arranged to meet at the first household at 7h30. I was there at 7h30, they came around 9h30 without communicating anything to me, but just giving weird explanations when they arrived. The ultimate highlight was then two weeks ago when I had spent the whole Tuesday arranging with four households that we would come the next day. During that whole day, I could not reach the emptier by phone. Until 19 o’clock, when he told me that he had another customer and would not be able to work on Wednesday. Although we had arranged to work together on that day. That was then the point when I fired him.

Next was pit emptier #2. Started off well the first two days. Third day, same story. We arrange to be at the household at 7h30, they show up around 9h45. Reason: he sent his guys to empty another household at 6 am and, surprisingly, encountered some difficulties there which delayed the process (which is a funny excuse as the whole business of pit emptying is basically one huge difficulty). When I confronted him on the phone, he even lied to me in the beginning about the reason for his delay. In the end, I also fired him. So tomorrow, we’ll start with pit emptier #3. Let’s see how that goes.

These incidences are, however, pretty well in line with something I read some weeks ago. I’m currently reading a book about cultural theory which tries to group cultures into different clusters and explain where cultural differences come from. At some point, the author (Hofstede) spoke about the reason why many Southeastern Asian countries developed rapidly in the 1950s and 60s (Tiger States) while almost all Sub-Sahara African countries didn’t, although both regions were roughly at the same point of development after World War II. One of the explanations he gave was a difference in future perspective which he found through surveys: Eastern Asian countries are very much oriented towards the long-term future and make economic decisions accordingly. Southern African countries, by contrast, are very much short-term oriented and live and think mostly in the present moment. According to his conclusions, this might be one reason why countries like Taiwan or South Korea managed to develop rapidly, while African countries didn’t.

And, although it might be a too simplistic explanation, in some sense I see this tendency also as an explanation for what happened with the pit emptiers. They prefer to squeeze in one more customer tomorrow and take the risk of losing the big customer who could give them work for several weeks.

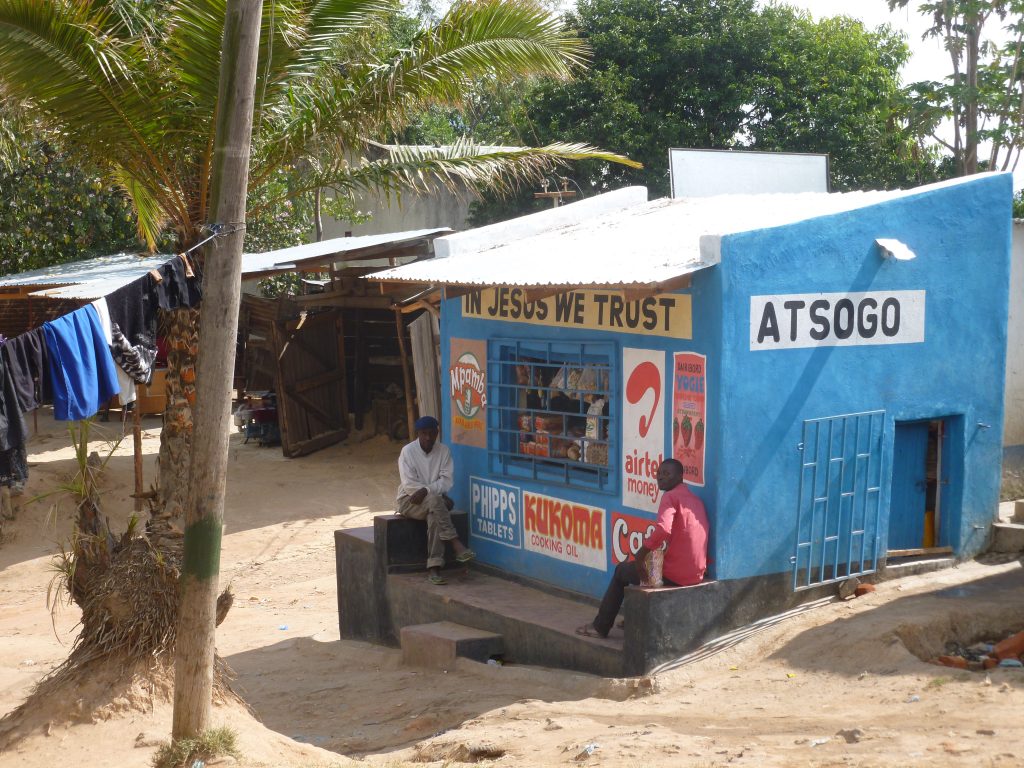

A very important topic here is religion. Over 80 % of the population are Christian, 13 % Muslim. And both religions are very present in everyday life. This starts with the call of the Muezzin five times a day which I hear in my room when I leave the window open. It continues with a large number of churches on every third corner of the city. And it becomes very clear when you talk to a Malawian for more than five minutes. At some point, they will always ask you “Do you go to church?” followed by an explanation in which church they are (there are several subgroups of Protestants, like Presbyterians and Seventh Day Adventist Church). It also happened already several times that I was asked “Oh, is this a rosary?”, referring to the rudraksha which I wear around the neck, a string of prayer beads commonly used in India. The highlight in that respect has been the visit to one of the households who had taken part in my facebook survey. The household owner greeted me warmly wearing a cap which read “God is Always Good”. When he invited me into his living room for the household interview, the walls were covered with images of Jesus and Mary and corresponding decorations. And finally, when he invited me to have lunch with him to thank me for emptying his toilet, he pointed at the food and said “Don’t worry – it’s already blessed.” And this might be an extreme case, but no matter whom you ask what they do in the weekend, they always go to church on Saturday.

What I find pretty strange about living here is that the society is split into two parallel universes: the black community and the (mostly, but not completely white) expat community. About 70 % of the city’s population lives in 21 low-income areas. On the contrary, basically all people from the expat community live in fenced-in, heavily protected houses with several employees. In between these two extremes, there is a black middle-income group who live in decent conditions, without employees and without electric fences. Through my work, I get to see households from nearly all income levels and I find the contrasts quite striking. On the one hand, communities where 11 households share one toilet and who don’t have a connection to the water grid. On the other hand, in the house where I live, 4 people are employed: Three guards ensuring 24/7 protection of the house (in addition to the electric fence, the alarm system, the dog and the steel bars in front of every window and door) and a housekeeper who cleans the house, washes the laundry, buys groceries, cooks once a day and does the dishes. And this is the normal “package” for all houses in the neighborhood where I live (except for the cooking which is a special feature of our housekeeper as he used to work as a cook before).

This brings up quite extremely the question of (white) privileges: The other day I was buying a package of juice in the supermarket which cost around 1.50 €. While buying it, I realized that many people could not really afford buying this juice. One of the guards of my house told me for example that he has to plan carefully in advance when he wants to go to his home village to visit his family as travelling by minibus costs around 4 €. From a European perspective, this might seem cheap, but as he earns around 60 €/month, it is in fact a significant amount of money for him and he surely cannot travel every weekend. With that as a background, the matter of privileges starts indeed with a bottle of juice, and not only with going to a European university or going on holiday for three weeks.

One consequence of these extreme differences in income is the fact that whenever you go to either a restaurant, a bar or a social event, you can be pretty sure to know at least a part of the other people. Since the group of people who can afford going to a restaurant or to a pub quiz is small, you’ll see the same faces at every occasion. These are mostly white, but not exclusively: Three people from the group of friends of Liz are from Malawi. They have, however, all studied in Europe or North America and now have high-level jobs as lawyers or doctors. So in that sense, they are also part of the privileged elite. Another funny thing I realized only recently is that there is nobody in my age group in the expat community. They’re all 35+, which is also a bit obvious as it is unlikely that anybody from Europe would come here to study (and there’s not enough people studying pit latrines who could accompany me :)). So now I always hang out with people in their mid-thirties, which is fun – just a bit unfamiliar.

Three weeks ago, I also started exploring the country a bit and travelled to Lake Malawi for two days with Liz and a friend of hers. Lake Malawi is the third largest lake in Africa (and the ninth largest in the world) and covers around one third of the area of Malawi. The lake is known for its large diversity of fish species: It has at least 700 species of cichlid fish (Buntbarsche), almost all of them endemic to the lake. As many of them are very colorful, they are increasingly popular with aquarium owners, and also some large aquariums in Europe have separate “Lake Malawi”-basins. Many of these fish can be seen when snorkeling close to a rocky shore of the lake. Despite this great natural beauty, there are almost no tourists around. The whole of Malawi receives around 40.000 tourists per year (for comparison: London received 19 million tourists in 2016), most of which are probably in fact working and simply enter the country on a tourist’s visa (like myself). So even though we went to “the most popular” place on the lake and it was a public holiday, there were only a few other tourists. It is hard to say why they don’t manage to attract more tourists. One explanation could be that it takes around 4-5 hours to reach the village from both the capital Lilongwe and from Blantyre. Also, the fact that electricity blackouts occur on a daily basis might make it difficult to develop high-class tourism that would attract more people. At the moment, the lodges on the lake are still very basic and, according to some long-term residents, the flair in the village hasn’t really changed compared to ten years ago.

On the way back from the lake, we had a small incidence: At some point, the road was blocked by a mob of obviously angry people. At first, we thought it’s a demonstration and pulled over to the roadside to let them pass. When they came closer, however, they indicated quite clearly and aggressively that we should turn around and go back. By the time we had turned around, the mob had reached us and people started hitting the car with their hands. Luckily, we were still able to drive away without any further damage. Taking a one hour detour, we also arrived home safely. When I asked Liz, she said that it was the first time in almost three years that something similar happened to her. And the next day, we also read in the newspaper that the violence was not at all directed against white people: A murder had happened in the village which made the inhabitants so angry that they decided to find and kill the murderer by mob justice. According to some sources, they managed to actually kill him, according to others, the police could rescue him. But also from my experience from the last six weeks, I can say that that was the only time when I didn’t feel 100 % comfortable. Else, people are very friendly 🙂